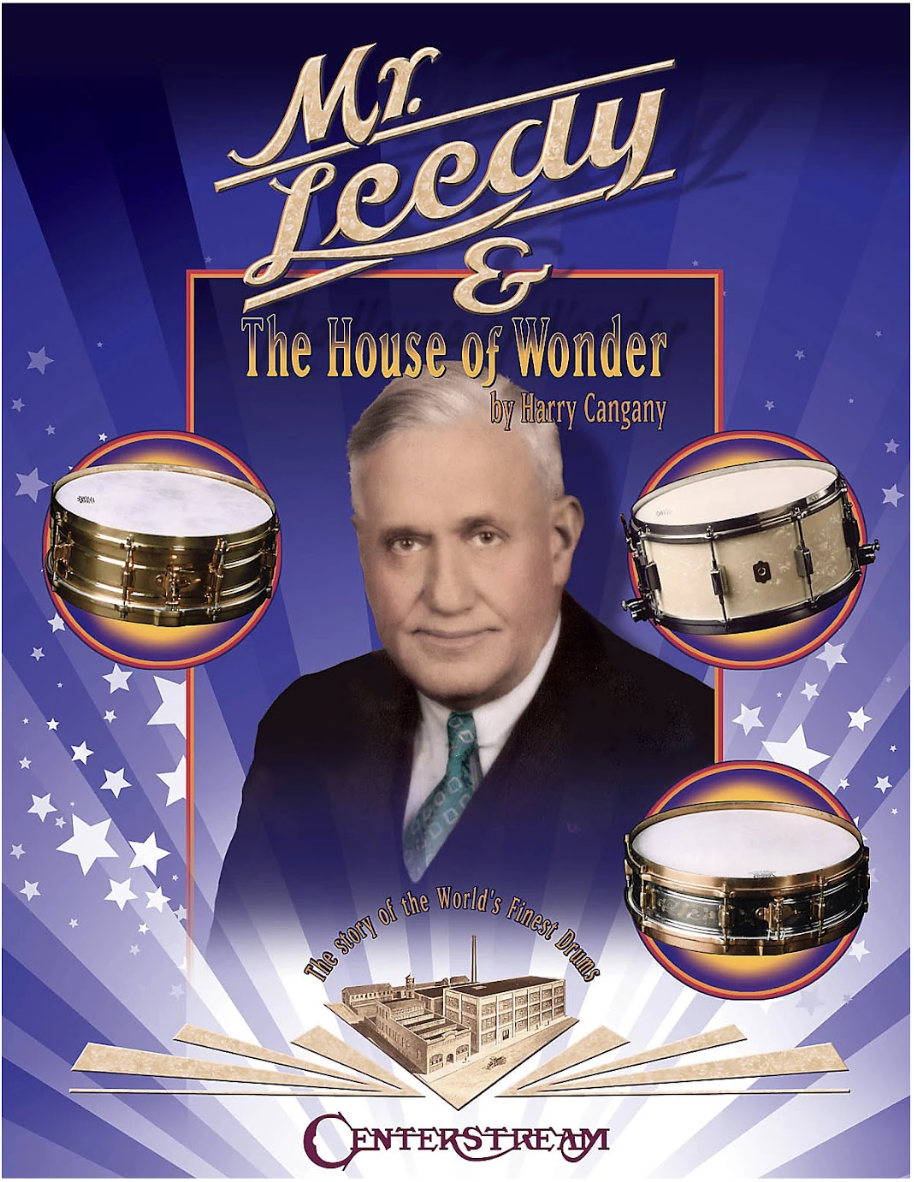

Musician: Ulysses Grant Leedy (1867-1931)

Ulysses Leedy was born in West Independence, Ohio, just south of Cleveland. At the age of seven, he was given a drum that had belonged to a Civil War drummer, and he began playing it for pennies for travelers at the local train station. As he grew, he followed the rails to jobs in bands in places like Cedar Point, even then a prime amusement park, and in 1895 to a position as a theater drummer in Indianapolis. It was an era when theater drummers were king, providing not just the music’s beat, but the gallop of horses and the roar of thunder for the performances, and eventually the silent pictures that played out on the stage. In addition to their drums and cymbals, crow calls and duck quacks were also a part of their inventory.

Leedy also had a mechanical knack. With a $50 investment, he began making snare drum stands in his apartment in 1898. Within two years, he was able to buy four adjacent lots and build his first factory, manufacturing sound effect instruments, bass drum pedals, and the snare drums themselves. He moved to a larger factory in 1910 and by 1920, with over $250,000 in sales, he was the world’s largest manufacturer of percussion equipment. His factory stood at the corner of Palmer and Barth, just west of where I-65 currently crosses Shelby Street.

Leedy and his staff were innovators. In addition to making the first modern snare drums, they created the earliest version of the vibraphone. This was the result of a request to chief engineer Herman Winterhoff (buried in Crown Hill Cemetery) to design an instrument that would combine the capabilities of a complete set of orchestra bells with a way to control the duration of sound using the same principle as piano pedals. In 1919, the factory built the giant 7’ bass drum for the Purdue Marching Band. Leedy became known as the “Father of American Percussion” and for 30 years, Leedy Manufacturing was certainly a leader in its field. Many of the best-known drummers of the day, including those in Duke Ellington and the Paul Whiteman orchestras used Leedy drums. But when movies switched from silent to having their own soundtrack, the market for specialty percussion instruments declined. Seeing that coming and with his own health declining, Leedy sold his business to Conn of Elkhart and retired in 1928.

Promotional literature of the Leedy Company includes this piece of advice to its customers: “Mistakes will happen in the best of regulated families. When we make one, let us know it. Don’t keep quiet and harbor an unpleasant feeling over what is nothing more than a misunderstanding. We will willingly admit an error and, after all, that’s all it amounts to, but if it gets by us and you say nothing, we both lose. Remember, Babe Ruth misses ’em once in a while.”

Leedy died early in 1931. His wife, Zoa Leedy, lived until 1974. They are buried side by side. Over the years, they have been joined by their sons and daughters, Eugene Leedy, Edwin Leedy, Dorothy Leedy Helgesson, and Mary Leedy Hampton. Their children’s spouses are also buried in the lot.