Juneteenth and Crown Hill

On June 17, 2021, President Biden signed into law a bill that established Juneteenth National Independence Day, June 19, as a legal public holiday. But what exactly is Juneteenth? What does it commemorate? And what are Crown Hill’s ties to this holiday?

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed by President Lincoln in 1862 to go into effect in 1863, gave emancipation to many enslaved African Americans, but not all. The proclamation declared, “all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” This, however, did not free individuals enslaved in states like Kentucky, which remained loyal to the Union, nor did it free individuals in Confederate States where the Confederacy was still in charge. As Northern troops swept across the south and took control of Confederate communities, small pockets of slaves were freed. When the South surrendered in April 1865, many plantation owners refused to acknowledge that the war was over and refused to “release” their enslaved workers. It took more federal troops marching further across the south to free individuals. The last group of enslaved African Americans freed by the Emancipation Proclamation was on June 19, 1865, in Galveston, Texas. It would take the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to end all legalized slavery in the United States in 1866.

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed by President Lincoln in 1862 to go into effect in 1863, gave emancipation to many enslaved African Americans, but not all. The proclamation declared, “all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” This, however, did not free individuals enslaved in states like Kentucky, which remained loyal to the Union, nor did it free individuals in Confederate States where the Confederacy was still in charge. As Northern troops swept across the south and took control of Confederate communities, small pockets of slaves were freed. When the South surrendered in April 1865, many plantation owners refused to acknowledge that the war was over and refused to “release” their enslaved workers. It took more federal troops marching further across the south to free individuals. The last group of enslaved African Americans freed by the Emancipation Proclamation was on June 19, 1865, in Galveston, Texas. It would take the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to end all legalized slavery in the United States in 1866.

Why do we celebrate Juneteenth? It’s a holiday celebrated on a date symbolic of the Black struggle for freedom and equality, with a focus on family and community. It is one of the earliest continuously observed holidays. African Americans in Galveston, Texas started celebrating Juneteenth in 1866, just one year after the end of legalized slavery there.

Why do we celebrate Juneteenth? It’s a holiday celebrated on a date symbolic of the Black struggle for freedom and equality, with a focus on family and community. It is one of the earliest continuously observed holidays. African Americans in Galveston, Texas started celebrating Juneteenth in 1866, just one year after the end of legalized slavery there.

What is Crown Hill’s tie to this holiday? There are 217 Civil War soldiers buried in the Crown Hill National Cemetery who were members of the United States Color Troops (USCT), and an unknown number are buried throughout the cemetery on family lots. As mentioned in our “Fathers of Crown Hill” article, Calvin Fletcher promoted the organization of USCT in 1864 in Indiana. Many USCT would carry copies of the Emancipation Proclamation with them and as they marched to various plantations and communities throughout the South, they read the Proclamation to those enslaved, informing them of their freedom.

Among the USCT buried here are:

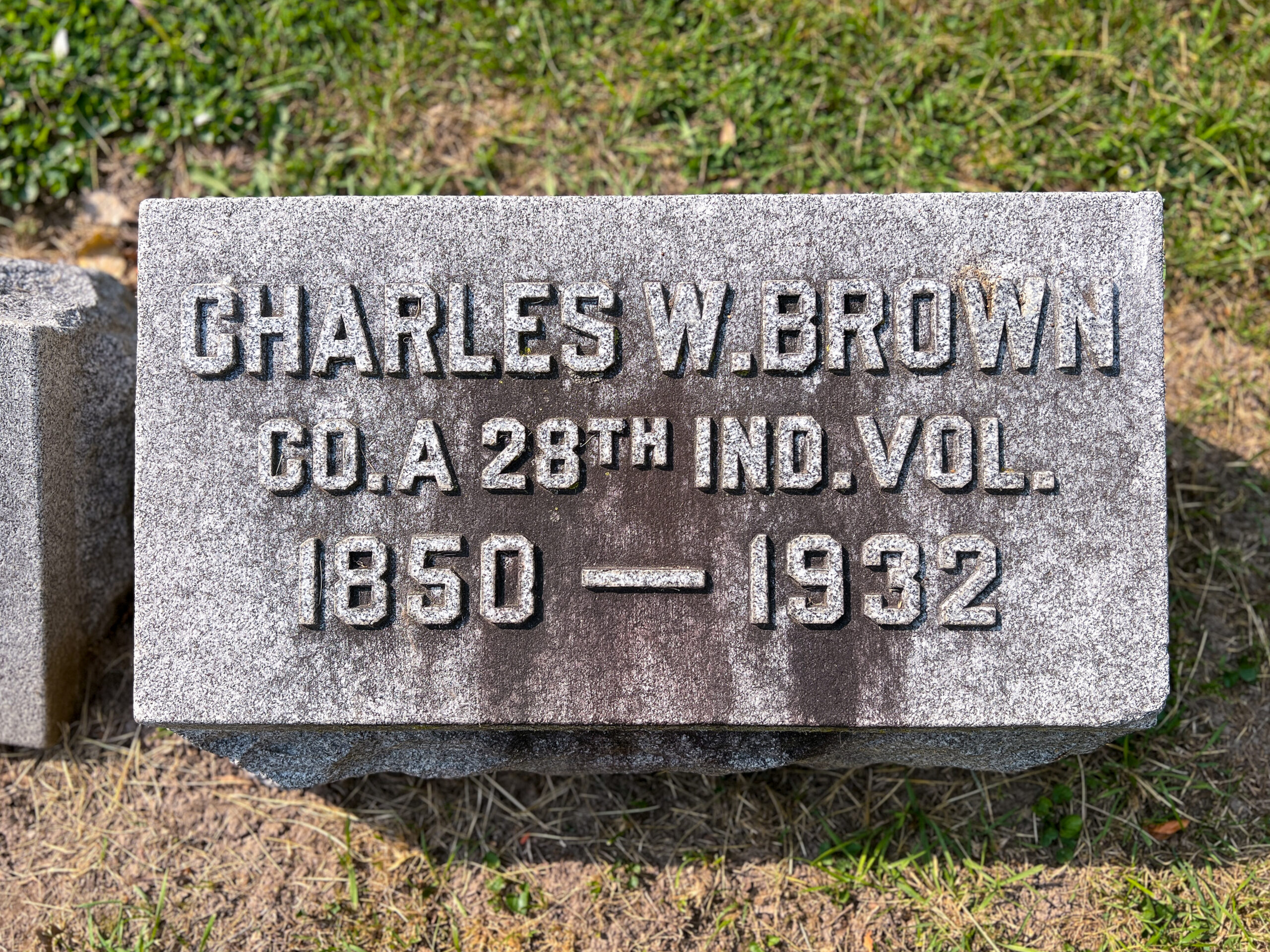

- Charles W. Brown (October 8, 1850 – March 28, 1932), the last surviving member of the Company A., the 28th regiment of the USCT. He was one of the organizers and leaders of the Martin R. Delaney Chapter of the GAR (The African American GAR Chapter).

Buried in Section 16, Lot 70; GPS (39.817590, -86.174995) - Edward Reed (AKA Reid) (1826 – May 28, 1900), worked as a carpenter in Indianapolis.

Buried in in Section D, Lot 2229, GPS (39.823488, -86.176397). His grave is unmarked. - Milton Robinson (1840-1930), who enlisted into the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment (memorialized in the movie Glory).

Buried in Section 9, Lot 1774, GPS (39.8176137, -86.17223342) – Crown Hill National Cemetery - Robert Bruce Bagby (1847-1903), moved to Indianapolis after purchasing his freedom and serving in the USCT. He was principal at Indianapolis Public School No. 17 (Booker T. Washington). In 1877, he became the first African American to serve on the Indianapolis City Council. At the same time, he and his brothers Benjamin and James established the city’s first Black newspaper, the “Indianapolis Leader.” In 1888, Bagby received a Master of Laws degree from Columbia University (now known as George Washington University). Bagby returned to Indianapolis in the 1890s and served four years as a deputy in the county clerk’s office and owned a successful law practice. His grave is unmarked, and the Crown Hill Foundation will be working in 2023 to find funding to secure a marker for this war hero, city politician, and Hoosier leader.

Buried in Section 27, Lot 143; GPS (39.817239, -86.169218). His grave is unmarked.

Along with the USCT burials, we have over 2000 White Civil War soldiers who fought during the war.

Along with the USCT burials, we have over 2000 White Civil War soldiers who fought during the war.

Another prominent Hoosier buried here is Reverend Willis Revels (1810 – March 6, 1879). He was Pastor of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in downtown Indianapolis, served as recruiter for Indiana’s 28th USCT Regiment, and supported the work of the Freedman’s Society, an organization which assisted newly freed Blacks. Rev. Revels is buried in Section 16, Lot 71; GPS (39.8176197, -86.1750811). His stone will be preserved in 2023 as a part of our 160th Anniversary through a generous grant from the Standiford Cox Fund, a part of the Central Indiana Community Foundation. (His brother, Hiram Rhodes Revels, not buried at Crown Hill, was the first African American to serve in the U.S. Senate, representing Mississippi from 1870-1871.)

Today we remember these individuals and the African American community as they celebrate freedom, equality, family, and community.